Read Sarah’s Full Introduction

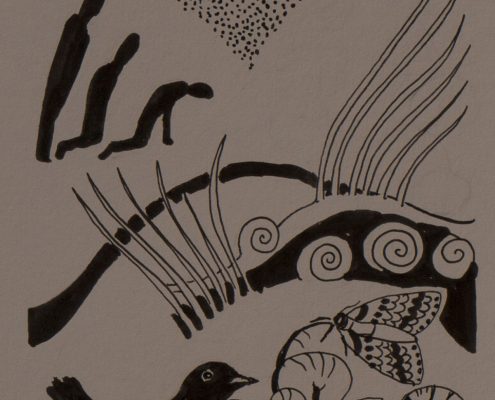

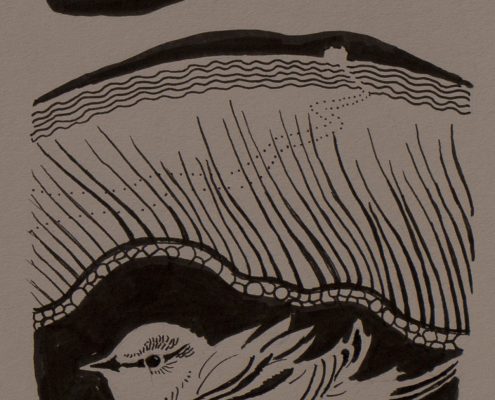

I remember when my father asked me to do a drawing for our very first Christmas card together. I must have been five or six years old, around the same age as my younger daughter Amelia. I was sitting at the big dining-room table and he gave me a black ball-point pen and showed me a picture of lapwings: the poem was 'The Lapwing's Egg'. I did the drawing very quickly (they take me a bit longer now) and it's still one of my favourites. I can't see a flock of lapwings without hearing his beautiful line from that poem: 'The dappled flight of lapwings’. Since then, our Christmas card collaboration has been a much-loved yearly tradition which I hugely enjoy: a chance for me to connect with my father’s poetry in a deep way.

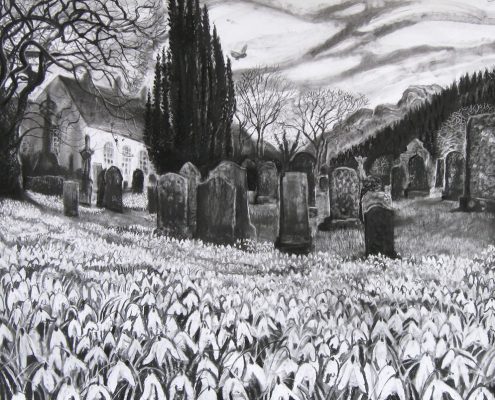

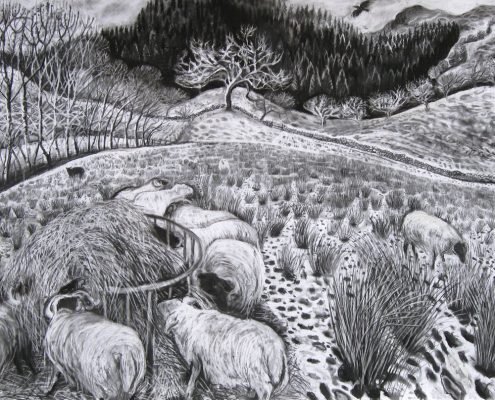

I have mainly used pen and ink for the Christmas cards, and occasionally watercolour, but in the past few years I've been using charcoal to make much larger interpretations of my father’s poems. This started with a commission from the Ulster Museum: a collaboration between artists and writers called 26 Treasures. I illustrated his poem 'The Brooch' about the golden salamander found in a wrecked ship from the Spanish Armada. I enjoyed the larger format, and, after moving to the Western Highlands six years ago, I began a sequence of illustrations in charcoal of poems by my father . Much to my delight, he had been inspired to write about our new home and landscape after visiting Lochalsh.

With poems such as 'Birth-Bed' and 'The Snowdrops', he has given me a magical way into the landscape: a lyrical route which helps me to interpret this new place. We are both fascinated by the mysterious hill behind our cottage, and Angel Hill became the title of his most recent collection. So we have coincided in a very natural way, and it has been a joyous experience for me to feel simultaneously close to the landscape (including its mysterious creatures and flowers) and close to my father through reading his poems and attempting to make images out of them. I find now that, as I read the poems, I see pictures forming in front of my eyes. This is similar to the process of looking at the world and imagining how I might use a stick of charcoal to draw a tree or a cloud.

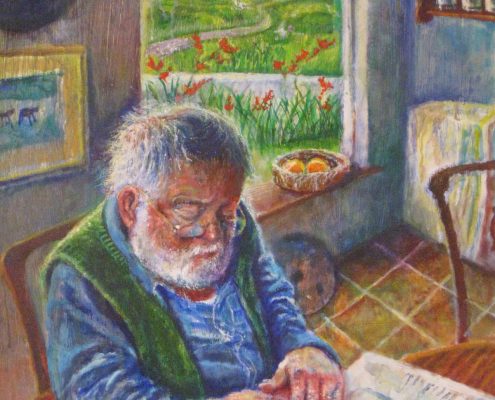

I feel blessed to have had the natural world open up to me through family holidays spent in a cottage in Carrigskeewaun: a remote townland in County Mayo and a profound source of my father’s poetry. Growing up in Belfast this was a very important experience for me. The extreme remoteness, the feeling of being totally immersed in the beautiful wild landscape of Mayo, was wonderful and still is. As a child my father taught me to stop and look, to listen. He taught me the names of birds and flowers, and to be receptive to the beauty of the world in all its detail. His poems do that too. This appreciation of beauty is something I'm trying to pass on to my own children.

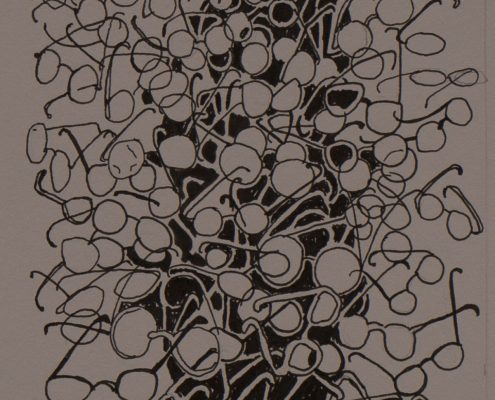

Now a new type of collaboration has emerged, thanks to Andrew Moorhouse and his Fine Press Poetry Publications (Andrew brings together poets and artists to produce beautiful limited editions). Our first joint venture was Sea Asters (2014) and the second A Dipper's Range (2016): both rich with flowers and creatures from Carrigskeewaun and Lochalsh. These are, as my father beautifully puts it, our 'soul-landscapes' which we have shared with one another. It has been a challenge to work within the narrow parameters required for printing – each page is printed individually from a metal plate – but I've enjoyed the restrictions. I've had to be strict with myself and try to reduce the large fluid movements which I employ when working with charcoal, and hone the marks down to the bare minimum using pen and ink, whilst still being expressive.

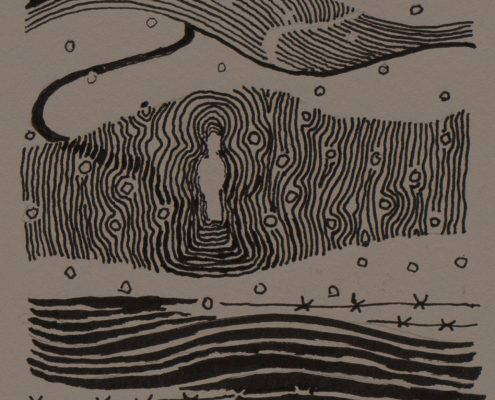

The third book is called Ghetto and is dedicated to Helen Lewis, who survived Auschwitz and Terezín before finding her way to Belfast, where she worked as a choreographer. She taught me dancing as a little girl. I had been thinking about Helen and reading memoirs such as her own wonderful book A Time to Speak and The Night by Elie Wiesel. I needed to do something creative with the emotions I was feeling. This was also the time when we were witnessing the horrendous 21st century suffering of the Syrian refugees. The poem 'Ghetto' was a way in. I nervously sketched out a few images and ideas of how I could present such a complex, powerful poem. I focused on the first three sections. It was an emotional process. I used my daughter Amelia as a model for the little girl in the second section: 'The little girl without a mother behaves like a mother //With her rag doll to whom she explains fear and anguish'. I also used my own photographs and bits and pieces to illustrate the first verse of ‘Ghetto’, which lists items which might be packed when you are abruptly forced to leave home: 'Because you will suffer soon and die, your choices//Are neither right nor wrong'. I believe that we must try to picture ourselves and our families enduring such hell on earth.

Eventually this led to the book Ghetto, with an illustration for each of the poem’s eight sections; also for several more Holocaust poems from previous collections, and a new poem 'Primo's Question'. It was a challenging task but I'm very proud of the book especially as right-wing xenophobia is simmering throughout Europe.

I am very grateful to the Junor Gallery for allowing me to show the drawings alongside the poems they illustrate: the collaboration with my father is a strand of my work which has always been very special to me. I also want to thank Andrew Moorhouse for inviting me to be the illustrator for his beautiful books. Ghetto will be launched in the gallery on Saturday 23 February, the day after the exhibition opens.

Sarah Longley, February 2019